Philip Hopper: Documenting the West Bank

Murals and graffiti on the Israeli separation barrier have been well documented by journalists and conflict tourists. The large symbolic painting of a crucified dove on the wall in Abu Dis was photographed in 2006. Like the wall this photograph is a segmented construction. The photograph consists of two contiguous photographs. The wall itself consists of thousands of intelocking or contiguous vertical cement slabs buried deep in the ground. In 2009 a new Palestinian roadway hugged the wall beside the crucified dove image, submerging a large part of the once impressive internationalist artwork. For Palestinians, moving students out of nearby Al-Quds University was more important than preserving an internationalist message. For most Palestinian residents the wall is aborrent and something, when possible, to be avoided.

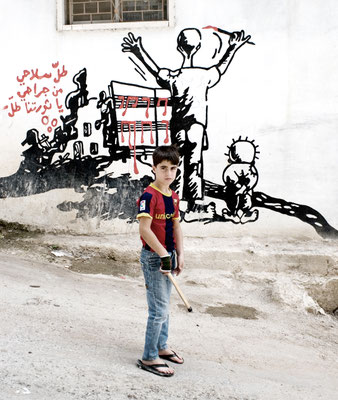

Images within Dheisheh Palestinian Refugee Camp grapple with ways to represent Palestinian refugee life without normalizing that experience. They help construct visual space in the Camp, providing a backdrop for transformational human activity. Those performative acts go beyond the painting of images. Children from the Camp identify with the abstraction of justice and also the heroic outward-looking martyr. A young boy stops rolling a tire down a steep camp street for the benefit of an unknown photographer. The mural text reads: "My weapon comes out and tells me not to stop (or to continue) to fight for our land." The conductor raises his “weapon” a baton – or is it a paintbrush? – above sheet music where the notes are red and dripping like blood. The ruins of some buildings are in the background. To the right Handala, the cartoonist Naj Al-Ali’s barefoot boy, looks into the image with us. Handala is a witness and so too is the boy whose outward gaze at the photographer serves as a focalizer for the audience of this photograph. In another image a young girl steps purposefully into the photographer’s frame. The children and adults in these photographs are not “discussing” a possible solution or outcome they are performing a complicated strategy of steadfastness. They are neither victims nor heroes. They are sumoud, (steadfast) posing for the camera consciously or unconsciously within the ongoing reality of a military occupation. I argue that these images within the camp are of much greater importance to local Palestinians as a form of nonviolent resistance to the Israeli occupation than anything painted on the separation barrier. My hope is that some of these images may become part of an archive that documents the non-violent response to that occupation.

For many Palestinians there is nothing more painful than Jerusalem which has essentially been annexed by Israel. Large Israeli settlement blocks surround the city as does the separation barrier creating a dagger-like image on the map. The higher elevations of the West Bank are split into northern and southern areas essentially splitting the West Bank in two. The Jordan Valley lies to the East entirely under Israeli military jurisdiction.

Clocks for Seeing

Clocks for Seeing